Senator Michael Kirby’s Senate committee’s call to bring discussion about mental illness out of the shadows at last seems to have some legs. People are talking, writing and, increasingly, making movies about mental illness. Since the 2006 Senate committee report, Canadian money has gone into Frankie & Alice, a drama about dissociative disorders starring Halle Berry; Kiefer Sutherland has starred in Mirrors about schizophrenia and more recently Melancholia; we have seen Craig Gillespie’s Lars and the Real Girl, featuring a person with delusional disorder; Atom Egoyan released Chloe in which there is a prominent role for a woman with borderline personality disorder; and now David Cronenberg has got in on the act with A Dangerous Method, which chronicles the relationships between Freud and Jung and between Jung and one of his patients. So if the media zeitgeist is a true reflection of popular culture, things are looking up for mental illness.

Well, maybe. Although in general the tone is much more sympathetic than it used to be, there is still a lot of confusion. This is partly because of the complex nature of psychological problems and their possible cures but also because clinicians, patients, families and policy makers all seem to have a different take on what the problems are and what needs to be done.

There is infighting in the field. Psychiatrists are characterized as considering mental illness as biological and needing pharmaceutical or physical cures such as electroconvulsive therapy or psychosurgery. A counter-stereotype is that of patient groups that are anti-psychiatry and focus on the social causes of mental illness such as poverty and abuse and the need for more humane approaches to treatment. Caught in the middle are families and caregivers who want their relatives kept safe or allowed to thrive in a community that does not care and policy makers who try to read public opinion when balancing spending on mental health against pediatric units and heart surgery.

Byron Eggenschwiler

But these stereotypes are not useful or accurate. In the real world, psychoanalysis was pioneered by psychiatrists as were many of the social interventions for mental illness. Psychosurgery is almost never undertaken and most of the people who have ECT ask for it.

The stereotypes are difficult to shift. They seem to be a result of our collective, but poor, understanding of the history of psychiatry. It is this history that Ian Dowbiggin investigates in his new book, The Quest for Mental Health: A Tale of Science, Medicine, Scandal, Sorrow and Mass Society. Dowbiggin is a professor of history at the University of Prince Edward Island and the author of six books on the history of medicine. This book considers movements promoting mental health from the 18th century to the present day.

Dowbiggin says his work reconstructs the winding road the world has followed since the French Revolution in the populist pursuit of psychological wellness … It is also the story of the resilient belief that the combined forces of science, medicine, government, public education, and professional expertise can make populations feel better about themselves.

But he has concerns with this belief and our current direction, and argues that an approach grounded in our understanding of the history of psychiatry is needed to find solutions. Otherwise, he says, the demands for psychological well-being will grow and “‘wretchedness’ and ‘servitude’ will be likelier than ‘freedom’ from the terrible ravages of mental disease as the new millennium unfolds.”

Dowbiggin’s thesis is built on three chapters that romp through 250 years of history followed by two chapters using modern examples to develop his argument. In “A New Egalitarianism,” Dowbiggin argues that between the American Revolution and the death of Napoleon a new understanding of what it was to be emotionally unwell was born, as was a new optimism that something could be done about it: “psychological well-being was not just an aim whose realization governments and their citizens increasingly desired, but—thanks to the march of science, the expansion of expert knowledge and the right level of state support—an achievable and laudable goal.”

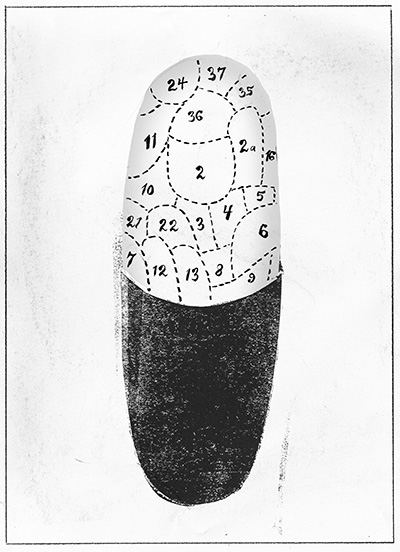

In its early days, though, the methods through which this was pursued were less than scientific. One was the theory of animal magnetism offered by the 18th-century Viennese physician Franz Anton Mesmer. He believed that space was filled with an invisible fluid that surrounded and also penetrated you, causing, among other things, depression. He massaged parts of the body where the invisible fluid had collected and so restored balance. He treated Mozart and was mobbed when he visited Paris because he held what was the dominant theory for treating depression at that time. Phrenology, the theory that personality could be identified and understood through the bumps on a person’s head, was also born in Vienna. Again it had popular appeal. Because it focused the causes of mental illness on the brain, some deem it the founder of brain research in psychiatry.

Although mesmerism and phrenology were not scientific in the modern sense, they captured the imagination of both the public and medical workers. They led to the creation of a new group of practitioners—psychiatrists—who claimed that their medical training made them the right specialists to treat people with mental illness.

In the 19th century, Dowbiggin argues, things really started to move. Governments began building asylums to house victims of mental illness. In this way the state started to take responsibility for the psychological needs of its population. Instead of the workhouse or jail, people with mental illness were to be offered treatment by professionals. This was a profound change in focus and it led to an increase in the number and power of psychiatrists.

Dowbiggin provides a fascinating insight into why psychiatry was so attractive to doctors. Until the mid 19th century, medicine was generally ineffective. Doctors had few treatments that worked and those that could cure, such as surgical operations, were generally performed without an anesthetic and often led to death by sepsis. There was no public funding or medical insurance and with their poor outcomes people tended to avoid medical practitioners. Doctors were often poor themselves:

Newspapers, novels, and broadsheets time and again depicted physicians as mired in grinding, embarrassing poverty. Their pauperism fostered the unflattering image of physicians perpetually on the make, a reputation that was popular in the first half of the nineteenth century, especially in the United States, where lax licensing laws made it difficult for regular physicians to distinguish themselves from herbalists, folk healers, patent medicine peddlers, and itinerant quacks.

By contrast, psychiatrists were seen as offering a service that was useful. They were well paid and well organized. Psychiatrists were the first groups of doctors to form professional associations and publish medical journals. Although there was suspicion about their power and scandal about the treatment of some patients, there was also agreement that society could not do without asylums.

The pace of change and the claims for psychiatry were even greater in the first half of the 20th century. Although country after country built asylums, still the majority of people with mental health problems were being looked after by their families. There was a growth in preoccupation with the difference between normal and abnormal psychology. As well, Dowbiggin argues, “an increasingly affluent and literate public, intent on unlocking the mysteries of the mind, dabbled in self-help approaches to mental wellness, including Christian Science, New Thought, and the Emmanuel movement.” At their roots, these movements offered individuals treatment based (sometimes loosely) on biblical teachings. Faulty reasoning and bad living were the causes of your problems and Christian psychotherapy—an extension of Jesus’s healing mission—was the cure. Faith was the key. While psychiatrists were skeptical of and somewhat patronizing to these movements, they benefited from them. Dowbiggin asserts that the faith-based movements in the United States opened the public to the idea that non-drug treatments could heal the mind. Because of this, when Sigmund Freud arrived in the U.S. for a lecture tour in 1909 as a neurologist, claiming he had discovered a way to help the mind mend itself without Christianity, he was welcomed. The age of psychoanalytic psychotherapy, the ego, id and superego was born.

In some ways this was a revolution, but it was still bedside (or couch-side) medicine. Perhaps the bigger paradigm shift came from Clifford Beers, whom most readers will never have heard of. After he had spent time as an inpatient in a variety of asylums because of depression and paranoia, Beers started a movement to “protect sanity” that endures today. His 1908 book, A Mind That Found Itself, led to the development of the concept of “mental hygiene” and helped to change both research and government policy. It allowed psychiatrists to look for opportunities beyond the walls of the asylum.

This was a period of great ferment and controversy, born from at least three forces that Dowbiggin chronicles: troops returning from World War One with shellshock and the perceived need to offer effective treatment, the fact that asylums were filling with the most severely ill people and it was becoming obvious that talking therapies were not curing them, and the fact that in the rest of medicine great strides were being made in finding biological cures (syphilis in 1910, insulin for diabetes in 1922, liver extract for anemia in 1926, and better surgical techniques and penicillin in 1928). Psychiatrists responded with their own “wonder cures”—types of brain surgery including lobotomy, insulin to induce coma as a treatment for schizophrenia and electroconvulsive therapy—the only therapy to really survive from that era.

Despite many demoralizing setbacks and frustrations, psychiatrists did not give up. And they were eventually rewarded in the second half of the 20th century. Like them or hate them, new drugs such as chlorpromazine emptied the asylums and offered hope of recovery to people with psychosis. Antidepressants provided an alternative to ECT for people who were depressed. And a process of deinstitutionalization began in the 1950s.

In the later chapters “A Bottomless Pit” and “Emotional Welfare,” Dowbiggin’s view of mental health treatments and services becomes clearer. He critically scrutinizes the increased reliance since the 1950s on psychiatrists and the mental health sector not just for treating illness but for “creating” wellness and happiness. The drug companies, the media, professional bodies and even political parties that espouse personal fulfillment are all given short shrift. And, of course, the expansion of diagnosis leading to more and more people with “mental disorders” is criticized. This leads to the claim from the book’s publisher that the quest for mental health has cost billions, with millions of people tranquillized, psychoanalyzed, sterilized, lobotomized and even euthanized … but with rates of depression today at an all-time high.

The book is a good read but not completely satisfying. This is in part because although it says that history is important and that we should listen to historians, it does not really explain why or how the insights from the book could actually be used to change anything that we are currently doing. Then there is the problem with representation. There is precious little information about movements anywhere outside the “western world.” That global voice, along with the voices of marginalized groups such as ethnic minorities within the western world, is rarely heard in these pages.

However, my main difficulty with the book is the fact that mental health and mental illness are conflated in an unhelpful way. These are very different concepts.

According to the World Health Organization, mental health is “a state of well-being in which an individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and is able to make a contribution to his or her community.” Mental health is “more than the absence of mental illness”; it is the “foundation for individual well-being and the effective functioning of a community.”

Mental illness is completely different: a pattern of thinking or behaviour that is generally associated with subjective distress or disability that occurs in an individual, and that is not a part of normal development or culture. Moreover, mental illness affects only a minority of people in their lifetime. The concepts for defining and treating it are firmly rooted in the medical tradition, not the broader society.

The book links mental health policy directions that aim to improve wellness with an expansion of mental illness treatment and prevention. I do not buy that linkage. Nor do bodies such as the Mental Health Commission of Canada, which clearly separates them in its draft strategy.

Improving mental health and treating mental illness require different sciences and skill sets. Although it may be sensible to offer Prozac as a treatment for depression, it would not be sensible to suggest putting it in the water to make everyone just that little bit happier. And yes, mental health specialists are constantly demanding an expansion of services, but it is for the treatment and prevention of mental illness, not to make us all more content.

People with mental illnesses have a greater array of effective treatments now than they have ever had before. They are also accruing more rights. Evidence from across the world demonstrates that treating mental illnesses increases a person’s ability to enjoy life, be part of a community and make money. If a sensible warts-and-all evaluation of organized treatment services is made, the conclusion is that generally they are a good thing.

And for mental health we see similarities. While the field is less well researched, the WHO has produced a whole dossier of evidence-based strategies that governments can use to improve psychological well-being. What promotes mental health and prevents mental illness is not a mystery. Unemployment, poor housing, domestic violence, poor employment, bullying, child abuse, income inequality, unsupportive communities, poor education are all factors—and the list goes on. But the WHO reports detailed, targeted, cost-effective strategies, starting in childhood, which can be deployed to stop these social factors leading to psychological problems.

The knowledge is there, the problem is convincing governments. It is difficult to convince governments when there is infighting and confusion.

There is clearly a need to learn from the past. Dowbiggin should be admired for taking on this task. Historical perspectives may help us to document what we know and rediscover things we have forgotten. They may stop us from making the same mistakes again. But that is not enough. If we are to really combat mental illness or produce a movement that will push us further toward mental health, we need research and new knowledge. We need to use all sources, including low-income and middle-income countries. And we need science so that we can make sure that new theories and treatments make a difference.

Dowbiggin may be skeptical that the combined forces of science, medicine, government, public education and professional expertise can improve the lot of people with mental illness. But if they cannot—given that all of us will either suffer from a mental illness or know someone who suffers from one—we are all in big trouble.

Kwame McKenzie is the medical director at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and a professor at the University of Toronto.