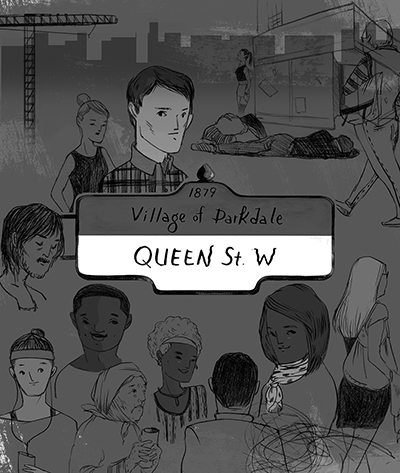

Stretching west between destination shopping emporia at Yonge Street and the grubby storefronts of Parkdale, Toronto’s Queen Street exerts a perennial attraction for writers, who use its contrasts for their explorations of urban life. Two new books—Confidence, a collection of short stories from consummate prose stylist Russell Smith, and Too Much on the Inside, by newcomer novelist Danila Botha—take on this neighbourhood in all its complex, contradictory and rapidly changing character.

Russell Smith, who has won a following through his Globe and Mail column as well as his books, hardly needs introduction. His early novels How Insensitive and Noise attracted attention for their urban emphasis, upsetting stolid pretensions about what counted as CanLit. The semi-pornographic Diana: A Diary in the Second Person anticipated Fifty Shades of Grey by a decade. Muriella Pent was the book that bit the hand that fed it, pillorying literary cliques with cutting satire. These works, particularly the latter, give credence to his publisher’s touting of Smith as “one of Canada’s funniest and nastiest writers.”

Smith’s most authentic groove, however, anticipated in both How Insensitive and Noise, and more completely articulated in Girl Crazy, is a distinctly sensitive, if also searing, engagement with middle-class masculinity. In his works—which can never quite be called confessional, given that he writes almost invariably in the third person—Smith’s mostly male protagonists are confronted in various ways with the distance between their desires (usually for sexual or social power) and their more prosaic destinies in the real world of delayed streetcars, unattainable women, demanding bosses and financial obligations.

In some ways Confidence revisits terrain explored in Young Men, Smith’s first collection of stories, though in the new book the men are, for the most part, no longer young. They are middle-aged mortgagees, burdened with wives and, in one case, a toddler, bound by commitments they can no longer easily escape and struggling with ambitions for things that seem relentlessly to evade them. Not that this stops them from trying, even as they come to grim sorts of recognition about the limits of their lives.

Suharu Ogawa

In “Raccoons,” for example, 40-something Leo, who is married to a passive-aggressive, incessantly Tweeting “mommy blogger” and is father to a “slapfooted” toddler known only as “the Bean,” has regular nightmares about the disintegration of his Parkdale home. He imagines that the ceilings leak, the foundations are caving in. His attentions are taken up nightly with the raccoons he fears have invaded his garage with their “smell of foreign feces” and broods of “slimy babies.” Leo is terrified of the raccoons, and of another secret lurking in the “man-sized” confines of his garage: a box of videocassettes depicting encounters with a bruised and drug-addled sometime lover who lives in a nearby basement apartment and keeps calling and threatening to firebomb his house if he does not return them. Smith almost too aptly articulates the dark absurdity of Leo scrabbling in the fetid garage for the videotapes, locating them at last beneath dusty gym equipment and a disused diaper pail.

Leo is unable to resist pressing play on one of a dozen tapes whose every moment he has memorized. His reveries are interrupted by the Bean, who demands to see, and his suspicious wife, who appears unannounced in the doorway. Later that night, following a failed effort to obliterate the evidence and silence his lover’s angry phone calls, Leo stands downstairs, listening to raccoons shuffling under the floorboards, and locks the doors, knowing with nauseating certainty that the real hazard is already well within the walls.

The claustrophobic tone and nightmarish sense of entrapment of “Raccoons” repeats in several of the other stories. In “Crazy,” a suicidal wife in the psych ward and a relentlessly ringing cellphone drive Smith’s unnamed protagonist to a rub-and-tug parlour, where he disrobes in a tiny room just in time for his phone to ring—his wife calling to report that she has been released. In “Fun Girls,” middle-aged Lionel finds himself consigned to the role of wingman to a group of beautiful women who drag him between cramped taxis and crowded clubs, have him pay for everything and then abandon him in an alley like an unwanted puppy. In “Txts,” a copywriter tries to soothe the sting of a failed relationship with Angelika, his ex, who prefers not to talk to him, by responding to misdirected text messages from a total stranger.

All these motifs collide in “Confidence,” the title story, set in a private club at which lawyers, entrepreneurs, executives, PR specialists—and three writers—have gathered in small groups. Confidence, of course, has multiple meanings, each of which plays out in turn. A well-known entertainment entrepreneur embodies confidence in the classic sense, choreographing conversations with glib self-assurance, observing at one point, “I like to control negotiations. It’s my background.” At the same time, he puts the “con” in confidence, eliciting private confidences he then uses casually against his interlocutors, and enticing attractive women from their dates before dismissing them like unwanted entrees. His guest, avant-garde novelist Lionel Baratelli (a name readers may remember from Young Men) vacillates between contempt and envy, keeping quiet because, as he says to one of the other writers, an inveterate graduate student, “I eat very well. I go to lovely houses. I get free trips from time to time.” When questioned about his work and his role as the club’s “tame smart guy,” he admits that he does not write any more, adding, “It was too difficult. I couldn’t stand the reviews. I couldn’t stand coming up with ideas. Never knowing if they were any good. I don’t have the, I don’t know. I don’t know what I don’t have.”

It is only the third writer, a young man whose membership remains a bit of a mystery, who writes silently in a leather notebook, senses dismissal from those around him and notes the need for the kind of confidence that goes beyond having a way with words.

The strongest story in the collection, “Gentrification,” inhabits a tense imaginative space between entrapment and exclusion. Smith’s depictions of Parkdale—with its “row of bars, grocery stores of conflicting ethnicities” and “bruised girls outside the McDonald’s”—foreground this tension, the dereliction of the main drag Queen Street contrasting with the putative peace of his protagonist’s home. The problem is that the gritty urbanity intrudes even up his quiet side street, into the basement apartment whose anticipated income enabled him to buy into the run-down but rapidly gentrifying neighbourhood. Still, when his two welfare-dependent women tenants skip rent and leave the empty apartment filthy, Tracy, a would-be erotic photographer for an amateur porn site, finds himself fantasizing sexually about one of them. Surveying Queen Street on foot, telling himself he is “doing research on the neighbourhood, perhaps in order to defend it better,” Tracy is attracted by young Roma women, whose “jeans were always a little too tight, the track jackets synthetic” but who “still made themselves look hot with their pudgy little bellies and their supermarket clothes.” Sensing an erotic as well as economic opportunity, he approaches a particularly appealing young woman, who rebuffs him with a gesture and a toss of her head. Humiliated and chagrined—how dare the exoticized Other refuse his gaze?—Tracy nonetheless contemplates the potential of his neighbourhood’s lingering dereliction. Even with designer lofts popping up and Montessori schools opening on the side streets, beyond them still lies “the flowing main street with its hungry gypsy girls.” Undaunted and with predatory intent, he resolves to rent a private mailbox and advertise online.

In Confidence, Smith does two things very well. The first is the precise and scathing social satire he is known for. In “Sleeping with an Elf,” for example, he lampoons a Parkdale bar whose name his protagonist can never quite recall—“something as trying-too-hard as Harvester or Barbershop or Bicycle Shed”—and its hipster clientele. It includes a full-bearded young man called “the farmer,” who wears an all-tweed ensemble and knee-length Wellington boots, and a tattooed woman wearing clothes right out of a 1940s Chatelaine magazine, complete with stockings seamed up the back of the leg. The other thing Smith does well is expose his protagonists in all their wretched vulnerability. In the midst of their bravado, they seem resigned to the consequences of their choices. There are even moments of grace in this, such as Dominic spying Christine through the window of their converted coach house at the close of “Elf,” sitting on the sofa in her bathrobe with a bottle of pop beside her, knitting and watching television. Something washes over him, “a terrible longing to protect her” from knowing he has seen her, and from the person he has become.

There are weaknesses in the collection. Some of the stories, notably “Crazy” and “Research,” end abruptly and lack the resolution even a short story requires. His women protagonists are little more than ciphers, defined mainly by their relationships with men (the exceptions are the lesbian tenants in “Gentrification” and Jennifer in “Confidence,” whose characters seem to achieve clarity through their rejection of men). Some of the stories seem retreaded, like old work brought out to flesh out the collection.

At the same time, however, Confidence reflects Smith at his best, a devastatingly deadpan chronicler of contemporary masculinity, and of social and sexual landscapes shifting tectonically like the urban spaces in which they are transacted.

If Smith’s protagonists are too often reduced to voyeurism, peering into lives they long to inhabit but can gaze upon only from the outside, the four protagonists of Danila Botha’s Too Much on the Inside are eager to escape from experiences that have alternately scarred or trapped them. Botha, whose first book (a collection of stories called Got No Secrets) drew praise for its compassion and urgency, brings similar sentiments to her interwoven portrayals of four new Torontonians of diverse origin (South Africa, Brazil, Israel and Nova Scotia) drawn to the openness and opportunities they sense Queen Street West might offer them.

Brazil-born Dez has opened CDRR (Casa de Rocha y Rolo), a hip, Brazilian-American fusion bar and restaurant on Queen near Dufferin, and it is here that Botha’s protagonists gather: Marlize, who has fled South Africa following a home invasion culminating in her brutal rape, and the murder of her mother and sister; Nicki, an Israeli unsure what she wishes to do with her life other than escape the cultural expectations of her Orthodox parents; and Lukas, a Nova Scotian who has walked away from a juvenile detention centre but brought his anger management problems with him. Marlize and Nicki work at CDRR, where Marlize begins dating Dez and Nicki takes up with Lukas, an occasional customer.

Both Dez and Nicki have tried settling in other parts of Toronto, Nicki in the “Orthodox Jewish paradise” of Bathurst and Lawrence, and Dez along the Portuguese stretch of Dundas West, where he contemplates opening a churrascaria and never needing to learn English. But like Marlize and Lukas, they are attracted to the street’s unique blend of glitter and grime. Nicki loves “the way the buildings look worn out in individual ways, some with fading graffiti, some with boarded storefronts, as if they each have a complex history that’s waiting to be discovered.” For Lukas the district offers him the option of anonymity: “I love the grime, the real-life feel of things, the mix of dollar stores and libraries, high school students and prostitutes, little kids and dealers. What I like most about my Parkdale neighbourhood is that I can disappear.”

Ultimately, however, even vibrant Queen Street cannot compete with the longing for the places and people Botha’s protagonists have left behind. At times Lukas chafes at the claustrophobia-inducing qualities of “living in a city where you can’t see the skyline ’cause of all the big buildings, where there’s so much noise you have to yell at the person you’re with when you step out on the sidewalk.” Nicki aches for the colour and even the contradictions of Israel, a country where she always knows where she stands. Dez’s competing commitments begin closing in on him, bringing his relationship with Marlize and his ownership of CDRR to a crossroads. It is at this point that the novel culminates in a series of loosely interwoven crises that press each of Botha’s protagonists to consider whether their destinies lie along Queen, or in other places where they might feel better understood. Their varied decisions reflect the opportunities and limitations of Toronto.

Too Much on the Inside deserves praise for representing Parkdale’s cultural vibrancy and diversity, and in doing so moving beyond the derelict-hipster dynamic characterizing so many works set in the neighbourhood. There is an admirable freshness and enthusiasm in Botha’s writing, qualities that do not inhibit her ability to describe dark and even violent events. At the same time, the novel is distinctly lacking a centre, perhaps a consequence of being told, relentlessly and occasionally repetitively, from the perspective of one character after another. The absence of any clear narrative resolution could be managed if the characters were drawn completely enough to carry the book, but they remain somewhat one dimensional, lacking strong enough connections to one another to remain compelling.

In Suburb, Slum, Urban Village: Transformations in Toronto’s Parkdale Neighbourhood, urban historian Carolyn Whitzman argues that Queen Street, and, by extension, any urban village, is understood best as a series of social narratives. Smith’s Confidence and Botha’s Too Much on the Inside represent meaningful additions to the story of the city.

Amy Lavender Harris is the author of Imagining Toronto (Mansfield Press, 2010). Her next book, a novel called Acts of Salvage, is forthcoming.