The study of Canadian foreign policy is in disarray. That is pretty much the conclusion Brian Bow and Andrea Lane reach in Canadian Foreign Policy: Reflections on a Field in Transition, their edited volume on what they describe as an academic discipline — known by the initials CFP — that has “been crumbling for twenty years or more but manages to survive in some form.”

It may well be that the practice of Canadian foreign policy is also in disarray, but that is not the subject of this book. In fact, the sixteen essays gathered here say very little about what ails our foreign policy, even though they imply that a revival of CFP scholarship would have salutary effects on matters of state. Indeed, the editors cite the need for a major review of the country’s foreign policy as a reason to revive the study of it.

What accounts for the decline of CFP when the challenges of actual Canadian foreign policy are more complex and demanding than ever? The editors note one major factor: “Many of the field’s most prolific scholars have recently retired or are just about to do so.” But that invites the question of why a new generation of academics have not filled the void.

The book’s contributors, all based at Canadian universities, offer a variety of takes on this puzzle. There is a confessional quality to many of their pieces. Some came to a belief in CFP through the internationalist inspiration of Lester Pearson and the “third way” idealism of Pierre Trudeau. Others have rejected the faith because it was not helpful in understanding the problems that have emerged following the Cold War, with which they were most concerned. Yet others disagree with the ontology of CFP, with its focus on states and state power. And some simply do not like the field’s ecclesiastical order: hierarchical, white, male-dominated, and opaque.

With challenges more complex and demanding than ever.

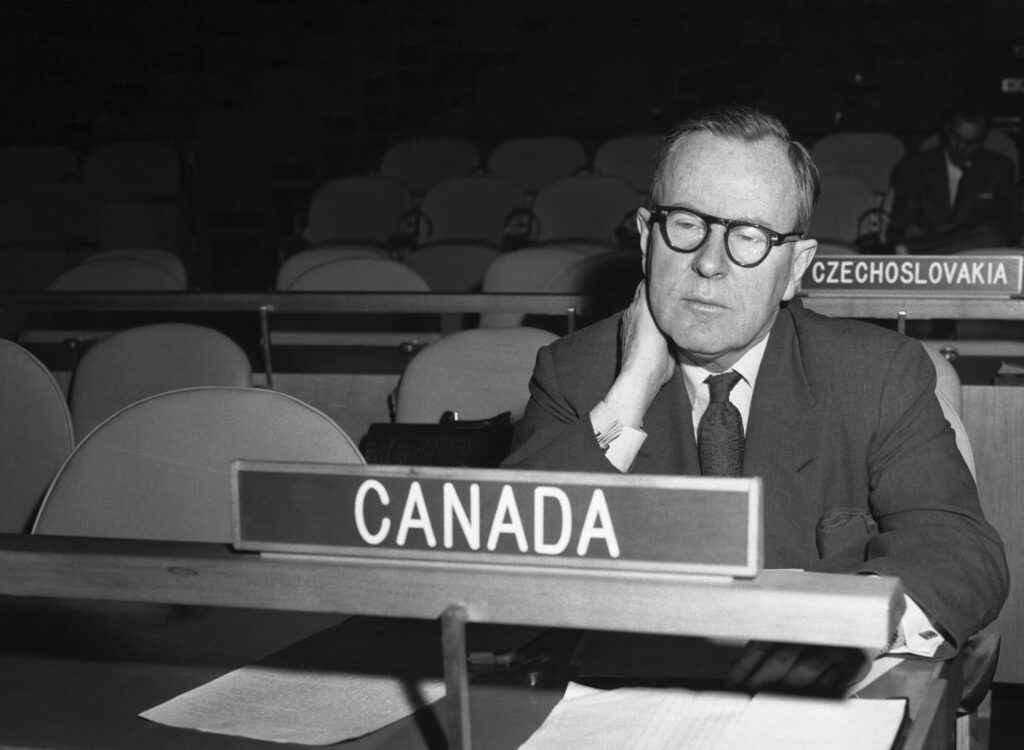

Bettmann, 1957; Getty

Bow, a political science professor at Dalhousie University, and Lane, a graduate student in his department, are not sentimental about a return to the heyday of CFP, but they are clear in their wish to reinvigorate it. Their commitment to revival is long-standing: they organized a “Generations project” workshop, which led to a special issue of International Journal, Canada’s oldest quarterly on international affairs, in summer 2017. They could just as well have described their initiative as a “Missing Generations project,” because they were unable to recruit any junior or mid-career scholars who specialized in CFP.

Alas, it appears there has not been much progress in the reinvigoration of the field over the past several years, which is perhaps why Bow and Lane assembled the current volume and offer in their concluding essay some ideas on how to bring about a proper revival. Their “manifesto” (as they self-mockingly call it) seeks to address many of the reasons cited by their contributors for not fully embracing CFP in their teaching and research.

Despite any epistemic, professional, and institutional objections would‑be practitioners may have, Bow and Lane argue that the moment for renewal is now:

At the risk of sounding trite, we suggest that the world needs more Canada and that Canada needs to know itself better if it is to be an effective global actor. For a long time, Canada has been a secure and comfortable country in a troubled world, usually trying to be helpful but always able to get away with not paying much attention to developments outside its borders. Today, the pillars that support its privileged position are being shaken, and Canadians will have to figure out where they fit into the world and how they are going to adapt to new global realities.

The essays in this book were written during the presidency of Donald Trump, though their authors were already looking beyond his administration and anticipating, correctly, a continued deterioration in Canada’s privileged position in the world. But there’s also an unstated chicken-and-egg problem about what really needs reinvigoration: the practice of Canadian foreign policy or the systematic study of it? Can one flourish in the absence of the other?

In my role as a legislator, I am generally agnostic about the contributions of various disciplinary faiths to questions of public policy. I am just as likely to draw on the expert insights of historians, economists, and political scientists as I am to listen to sociologists, climatologists, and psychologists. But as an occasional “academic tourist” in the land of CFP, I am sympathetic to Bow and Lane’s worry that the lack of disciplinary focus could result in an incomplete understanding of domestic and international issues that impinge on the actual making of foreign policy.

Consider, for example, how Canada should respond to efforts by the United States to decouple from the People’s Republic of China. The historian might offer lessons from previous episodes when Ottawa diverged from U.S. policy; the economist might calculate the pecuniary costs and benefits of doing so again; the political scientist might speculate about electoral consequences; the international relations specialist might muse about retaliation; and the sociologist might reflect on impacts on Canadian society more broadly. Into the fray would come a CFP specialist who is able to work with the analyses of these disparate disciplines to offer a holistic picture of the implications for Canada and a framework for how Ottawa should respond.

Would that it were so.

In reality, the stitching together of different perspectives and, by extension, the balancing of interests to come up with a response is the work of foreign policy practitioners — meaning civil servants, who are usually second-guessing the politicians. They are likely to have drawn ideas and insights from scholars, but in the current climate of maximalist and diffuse public consultation, the viewpoints that emerge as policy are as likely to come from a town hall discussion as they are to be handed down from the ivory tower.

Perhaps the devaluation of academic contributions has contributed to the jaded view of John Kirton, who directs the G7 Research Group and the G20 Research Group at the University of Toronto. In his essay, he acknowledges that CFP experts have had limited impact on policy since the Second World War, even if they have contributed richly to the debates that have shaped it. Controversially, he argues that their impact was greatest under Paul Martin, because as prime minister he had the “most ambitious, innovative, transformational agenda to replace that of his Pearsonian predecessors and . . . needed scholars to help him do the job.” Kirton cites two particular accomplishments under Martin: the Responsibility to Protect doctrine and the Leaders 20 institution, bringing together the heads of the twenty largest economies. But, given the hollow track record of both, Kirton’s view is not exactly a ringing endorsement of scholarly sway.

It would, however, be too instrumental a view of CFP to measure its success purely in terms of direct impact, even if some scholars might judge themselves by such a metric. Unmoored from theory, uncertain of influence, and unclear about objectives, younger academics in particular can be forgiven if they steer away from the treacherous waters of normative CFP scholarship for fear of reproach from their more senior colleagues.

Yet, as far as Kim Richard Nossal of Queen’s University can tell, there are still CFP courses aplenty across the country: eighty-one offerings across fifty-seven institutions as of 2017. In an essay that “seeks to trace the rise — and slow evanescence — of a distinct CFP professoriate in the Canadian academy,” he speculates that there is persistently strong demand for such material from undergraduates but a chronic shortage of professors to teach it. Shunned by junior academics who face relentless pressures to meet tenure requirements, these courses end up being taught by sessional lecturers of the precariat.

It is unlikely that traditional academic departments will deign to debase their standards anytime soon by recognizing the intrinsic value of CFP, which is why any revival is more likely to come from low-church centres of scholarship, such as schools of business, public policy, global affairs, government, and other interdisciplinary topics. It is typically at such places that the appointment of practice professors is catching on — in recognition of the value of professional experience as a unique source of knowledge. Whether a junior scholar can craft a successful academic career as a CFP specialist at such a hub, however, is yet to be seen.

A different sort of CFP incubator can be found in think tanks and non-university research centres that focus on international issues. Here, there has been a renaissance of sorts, with the establishment of several foreign policy institutes in recent years, including the Institute for Peace and Diplomacy, as well as the expansion of foreign policy topics among organizations that have traditionally focused on domestic issues, such as the Canada West Foundation. This shift has to do with the blurring of foreign and domestic policy questions as much as with a revival of CFP as such, but the discipline’s champions would surely do well to get on the bandwagon.

Regardless of the state of CFP, what really matters, of course, is the actual practice of foreign policy. I agree with Bow and Lane that a stronger CFP community would produce a richer range of ideas and insights for the making of policy, but I am pessimistic about the current conditions for knowledge exchange among experts, officials, and the political class.

It has become fashionable among CFP scholars and tourists to call for a major review of Canada’s international policies, but this kind of call comes up with predictable frequency, usually around a general election. These reviews — or “updates”— are heavily conditioned by the current temper of the most vocal public, even more so today because of social media, and weaponized by partisan forces for electoral gain. The ideas contained therein are often either vague and anodyne or so specific that they are rendered passé within months of release. It is no wonder that senior foreign affairs officials are usually among the least enthusiastic about such exercises, because of the complicated hoop-jumping that comes with the production of the necessary documents and the limited utility that they offer when completed.

Even so, there is no question that Canada needs to rethink its international priorities and positions. It is not clear, however, that our leaders, of any political stripe, understand how profoundly the certitudes of our place in the world have collapsed in recent years.

Joe Biden notwithstanding, the United States cannot be trusted to look after Canada’s interests. Regardless of how long Xi Jinping remains in power, China will pursue its economic and political objectives with cold tenacity. And the ongoing clash of interests between the two powers will force Canada to make choices that will please neither. Consensus among Western allies will last only until national self-interest overrides lip-service solidarity. The failure of lofty policies to deliver a better standard of living will fuel the domestic rancour that gives rise to extremist politics. For its part, climate change will have a more rapid and disruptive effect on the Canadian geography and economy than we are prepared for. And that is just for starters.

Until we are ready to see these verities, it will not be propitious to attempt a major review of Canadian foreign policy. What we need for the immediate future is a pragmatic approach to global affairs that privileges autonomy and flexibility, with the goal of improving the welfare of Canadians while maintaining our reputation in the world as a fair-minded internationalist. A revival of the CFP community will not provide us with all the answers — but it could help us muddle through.

Yuen Pau Woo is an independent senator representing British Columbia. Previously, he was president and chief executive officer of the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada.